written by Tomoko Sato

I did a residency in Taiwan from October 2023 to May 2024.

Throughout the six months, my research was supported by Thinker’s studio and also by Ting Shuo hear say (Tainan) during my stay in Tainan from January to February.

The purpose of the residency was to research the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan.

In Japan, I have been researching the city of Tokyo since 2020.

Based on the idea of “Imagining Another Tokyo,” which Taro Okamoto, a postwar artist, presented in 1964 which he called “Obake Tokyo,” I am researching the path Tokyo has taken and conducting fieldwork in the present. As a result of this work, three lecture performances have been produced in the past.

Contents of the lecture performances are as follows:

An introductory chapter that retraces the footsteps followed by the monster Godzilla in the 1954 movie “Godzilla.

The first chapter follows the blackbird “crows,” which are too numerous in Tokyo.

The second chapter departs from the Sogetsu Art Center, which became a center of ikebana and avant-garde art after the war.

In confronting Tokyo through this project, I learned that Tokyo was officially born in 1868. Having lived around Tokyo for granted for years, I was surprised to learn that Tokyo was founded not too long ago, about 150 years ago.

I also learned that during those 150 years, Tokyo was once the imperial capital and military capital.

There are not many traces in the present day, but they can be found.

In the process, I came across some lands that Japan had colonized.

I knew that Japan had colonized some areas.

But I knew nothing of the details.

This lack of knowledge, I thought, was also connected to my lack of knowledge of Tokyo, and also myself.

Then I came to Taiwan.

========

The first thing that surprised me when I arrived in Taiwan was that there were stories about the Japanese colonial period everywhere, including historical museums and art museums.

The content of the stories was not about whether the period was good or bad, but that it was there to reflect on the time that the land of Taiwan had passed through.

I understood It was about “what kind of place we are in and who we are here now.”

“What is this place where I am, and who am I here now?”

I have been asking myself this question during the whole period of my residency.

========

“What is this place where I am, and who am I here now?”

Thinking about this question alone was too difficult.

The more I learn about a place, the more new layers I see, and the more I meet people, the more I see people I could not see, and it was like a mirage moving in front of my eyes.

“Let’s read this book together.”

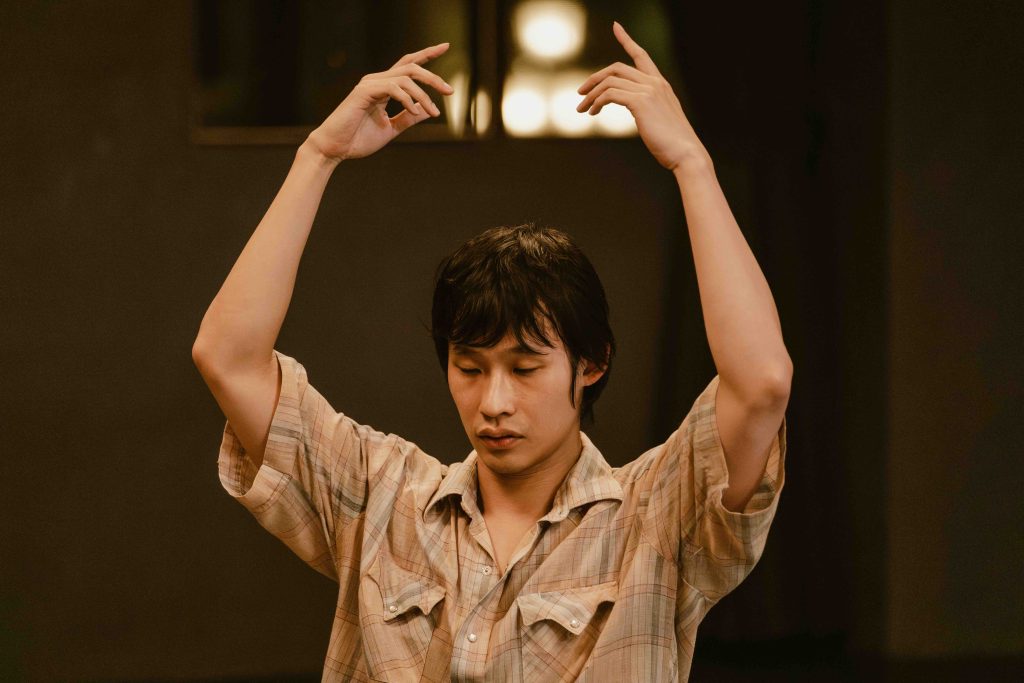

It was then that I received a message from Taiwanese artist Li Wen-Hao.

========

The book that Wen-Hao sent me was,

“A Love Story Before Daybreak” by a Taiwanese writer named Wong Nao (1910-1940).

The main character, who has come to Tokyo from Taiwan, monologues his thoughts on “love” to a woman, who is assumed to be Japanese, until daybreak.

It is a short story written in Japanese during the Japanese colonial period.

Wen-Hao read the Mandarin translation version, and I read the original one in Japanese.

I wondered in which language he would have continued to write if he had lived until after the war.

In the novel, the main character says to a woman,

“Where was I born? I am late to say this, but I was born in the South. You were born in the snowy north.”

Love, romance, romanticism. These feelings gave me a strange sense of distance.

We read another novel, “Zanzetsu,” written by Wong Nao.

The main character is a Taiwanese who lives in Tokyo and works in the theater. There is a Japanese woman from Hokkaido who comes to Tokyo and works in a café, and a Taiwanese woman from Tainan who comes to Taipei and also works in a café.

Both Taipei and Tokyo had cafes where women served customers in the early 20th century. Many women from the countryside came to live and work in these cafes.

In Tokyo, there was also a café called “Oolong Tei” that served Taiwanese oolong tea.

In the novel, the main character, a Taiwanese man, says to a woman who came to Tokyo from Hokkaido and works at the café,

“This woman is still pure, just like the snow.”

There is a novelist in Japan named Fumiko Hayashi (1903 – 1951).

Hayashi was invited by the then Governor-General of Taiwan to visit Taiwan in 1930.

In 1928, Hayashi, who was seven years older than Wong Nao, published her autobiographical novel “Horo Ki (Wandering),” in which she speaks the following lines while working in a café:

“Life has become a real bore. Working in a place like this makes me feel so bored, so bored, that I want to shoplift. It makes me want to be a bandit, a yin-bai (some kind of prostitute).”

========

After some online discussions and having conversations over many cups of coffee at cafés in Taipei, Wen-Hao and I decided to create a small performance.

It reminded us of myself, originally from a snowy region of Japan, and Wen-Hao, who was born in the greenery of Taipei, Taiwan.

The idea was to create a time to think about love, romance, fantasy, illusion, delusion, purity, purity, savagery, and so on.

It somehow felt important to think about the topics to reflect on the Japanese colonial period that we have been researching together, as well as the feelings we now have about the land we have both lived in.

During the performance, being surrounded by the aroma of the oolong tea we had prepared, Wen-Hao talked (and sometimes sang) about snow and the melodies of songs that came to Taiwan from Japan, and I talked about some of the trees I had encountered in Taiwan.

Some of the trees I mentioned were the giant king palm, the banyan tree, and the Taiwan cypress.

Even in the streets of Taipei and Tainan, I was overwhelmed every day by large trees that I had never seen in the cities in Japan, but these trees I mentioned were especially special.

Those trees are something that I can still see them, touch them, and listen to their stories. They also had a deep connection with the Japanese colonial period and seemed to predict the same kind of romance and fantasy that the Japanese of that time and I have today. Along with the huge trees in front of me, there was a landscape that stirred my emotions.

I’ve already written too much for this journal, so I’ll skip the details of each tree here.

However, I felt some sense of romance towards the trees, and at the same time, a sense of contradiction was also there with knowing the context of the trees.

I wanted to think about these feelings along with the novels of Wong Nao.

========

“What is this place where I am, and who am I here now?”

It is essential to look at this question from the perspective of history, society, and facts (such as they are).

At the same time, we cannot escape the fact that emotions, fantasies, delusions, and the like, are always in front of us.

What kind of narratives can we create from these situations and share them with the people in front of us?

I hope that this project will be a continuous journey,

just as Wong Nao has been on a journey with his novels.

========

At the last, I want to thank Li Wen-Hao, Lee Vivien, Hong Ching-Ting, Nathan Liao, Alice Hui-Sheng Chang and Nigel Brown (from Ting Shuo hear say) for all their support and contribution to my residency.