文/周寬柔

在Perth Moves當中的Movement Together工作坊由My Studio Performance Maker’s Collective(簡稱MSPMC)主辦。MSPMC隸屬於當地障礙者支持組織My Place,由不同障別與非障礙者的藝術家組成。所共作出的作品形式包含但不限於舞蹈、劇場、錄像和繪畫等。內容不只以障礙者為主體,創作過程更試圖以障礙者主導(disability lead)出發。

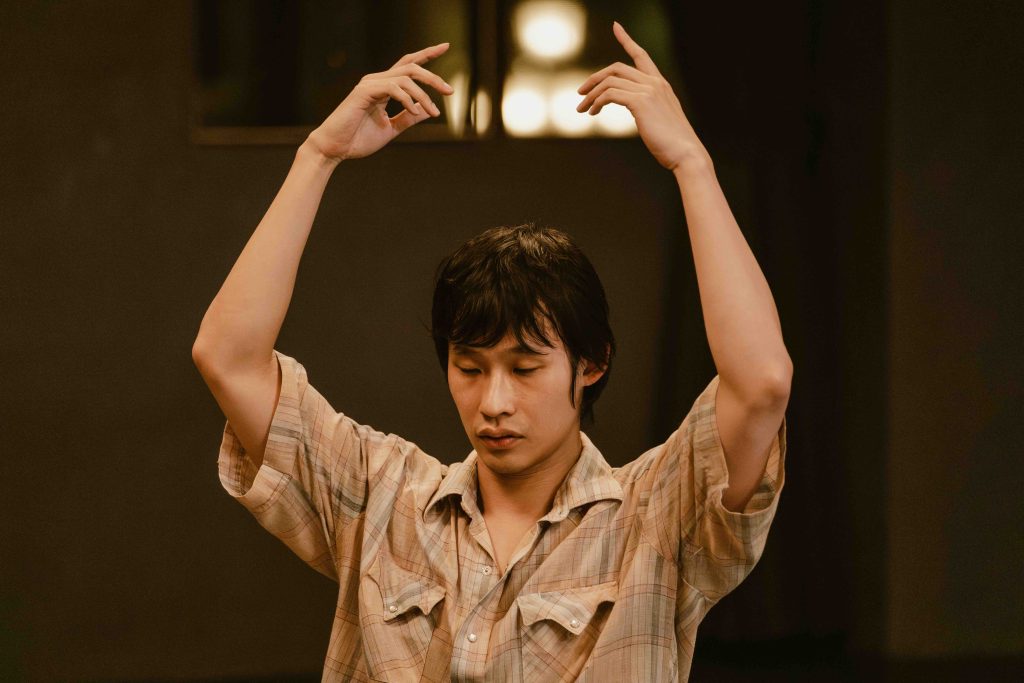

在一個舞蹈的排練場裡,有編舞者、舞者、排練助理,或許還有設計們。那麼多不同的個體共處一室,眾人的身體由編舞者來主導。從空間分配到時間掌控,整個排練室都是編舞者的身體交織創作意念的具象體,而我們對這此也習以為常。但在不同障別與直立人共處一室環境中,如何共創?我最好奇的並不是他們的方法是否有達到所謂的平權(根據誰的標準?),而是在這其中試圖靠近平權、因應個體而不斷轉向的實驗性和對於人的關懷。

每天我們都從聊天和即興舞蹈開始,除了暖身、打開覺察,更是建立安全感的必要步驟。聊天內容從自己當下的狀態,分享到對於昨天的回應(reflection)。我很喜歡工作坊大量使用reflection這個詞,「映射」的意象在這個場域裡更加成立。不同於直立人的社交模組,腦性麻痺處境和自閉症處境的參與者都有自己的語言表達方式。從聲音到思考、語言邏輯,可以在對話裡看到個體最純粹與直接的映射。慢慢的,在這個場域裡我也更放鬆的表達自己,在聆聽他人的需求之後更懂得聆聽自己的需求;即興暖身則是更直覺地將自己安放進這個場域。無目的的動,或是與自己不熟悉的身體共舞。就兩個身體產生可看見的連結來說,無效的次數可能多於有效。但無效後的選擇,無論是暫時休息還是換一個方法嘗試,通常都比有效的經驗更可貴。

在他們所研發的接觸即興方法中,我們從單點式的碰觸(Join)、滾動(Roll)和眼神接觸(Eye Contact)中學習如何小心翼翼的觸碰、保護彼此的身體,也學習如何因應不同個體的狀態做調整。例如碰到對於眼神接觸較敏感的夥伴,視線可以友善的轉移至鼻尖,再依狀態循序漸進的調配。我們也嘗試鏡像(Mirror)彼此的身體,跟最常見的歧視行為-模仿身障者的身體不同的是,鏡像是具同理的雙向溝通,不帶符號意涵的去向另一種身體姿態學習。

「如果世界的動態以障礙為中心會怎樣?」在很多練習裡我都感覺到這個問句的可能。當結構即興中的角色、時間、空間以障礙身體出發,障礙不再是缺陷而是編舞。編舞是一種賦權,從空間位置的關係體現障礙身體如何改變一般編舞者和舞者的空間權力關係。編舞可以是很簡單的看見動態,感受、回饋並作出主觀的選擇,對於不能自如跳舞的身體來說,編舞也是一種舞蹈的意識。

而對於時間的安排,我們花了很多時間在等待自己跟他人。就中文的語境,很類似「讓子彈飛一下」。連分組我們都花很多時間,不以快速粗暴的方式分類群體,而是讓每個人好好感受今天的需要並作出選擇,這在當代社會中聽起來如此奢侈,卻不應該奢侈。在這些集體沉默、沒有肉眼可見的事情在發生的時間裡,卻讓我感覺到無比的放鬆和信任,對此我非常感激。

總結在工作坊裡的學習,其實是聽起來很簡單的在involved all the individuals的情況之下spend time togther和share the same space。但要如何更平權、更通用的spend and share是要花很多時間事前準備和溝通的。即便準備好了,面對多變的個人/群體狀態卻需要具有同理意識的應變能力,這是很不容易的。而無論是disability or not,每個人在其中產生的感受與情緒,要怎麼安放、願意表達或協調,也是這個工作機制的一大挑戰。與障礙者的工作經驗可以很直接應用在各種藝術或非藝術的集體工作裡,或甚至面對「自我是一種集體」的處境當中。反思回我去年所主辦的情慾身體工作坊,也有相同的需要。一個有機且包容的場域第一步或許是先看見個體與群體的交織性(intersectionality),依其產生多變且非古典的空間動態、給予足夠的時間製造連結,並更樂觀的看待失敗。

The Beauty of Delay – Movement Together Workshop

The Movement Together workshop within Perth Moves is organized by My Studio Performance Maker’s Collective (MSPMC). MSPMC is affiliated with the local disability support organization My Place, comprising artists of various disabilities and non-disabled individuals. The collaborative works produced encompass forms such as dance, theater, video, and painting. Not only focusing on individuals with disabilities, the creative process attempts to be disability-led.

In a dance studio, there are choreographers, dancers, rehearsal assistants, and perhaps designers. With so many diverse individuals in one room, the bodies of everyone are directed by the choreographers. From space allocation to time management, the entire space embodies the choreographer’s physical body intertwining creative ideas, which we have grown accustomed to. However, in an environment where individuals with different disabilities and non-disabled individuals coexist, how do they collaborate? What intrigues me most is not whether their methods achieve so-called equality (by whose standards?), but the experimental nature and care for individuals that attempt to approach equality and continually adapt within it.

Every day, we begin with chatting and improvised dancing, not only as warm-ups to open awareness but also as essential steps in establishing a sense of safety. Conversations range from our current states to reflections on yesterday’s experiences. I particularly appreciate the frequent use of the term “reflection” in the workshop; the imagery of “reflection” is even more valid in this field. Unlike the social norms of non-disabled individuals, participants with cerebral palsy or autism have their ways of expressing themselves linguistically. From voice to thought to linguistic logic, one can see the purest and most direct reflections of individuals in conversation. Gradually, in this space, I have become more relaxed in expressing myself, and after listening to others’ needs, I have learned to listen to my own needs. Improvised warm-ups intuitively place oneself in this space, involving purposeless movements or dancing with unfamiliar bodies. In terms of visible connections between two bodies, the number of unsuccessful attempts may exceed the number of successful ones. However, the choices made after failures, whether taking a temporary break or trying a different approach, are usually more valuable than successful experiences.

In their developed contact improvisation methods, we learn how to touch each other carefully and protect each other’s bodies by Join (single-point touches), Roll, and Eye Contact, as well as how to adjust to the different states of individuals. For example, when encountering a partner sensitive to eye contact, the gaze can kindly shift to the tip of the nose, gradually adjusting based on the situation. We also attempt to mirror each other’s bodies. Unlike the common discriminatory behavior of imitating the bodies of disabled individuals, mirroring involves empathetic two-way communication, learning from another body posture without symbolic implications.

“What if the dynamics of the world were centered around disabilities?” I often sense the potential of this question in many exercises. When roles, time, and space in structured improvisation originate from disabled bodies, disabilities are no longer seen as defects but as choreography. Choreography becomes an empowerment, showcasing how disabled bodies change the power dynamics of space for both choreographers and dancers. Choreography can be as simple as observing dynamics, feeling, providing feedback, and making subjective choices. For bodies that cannot dance freely, choreography also becomes a form of dance consciousness.

As for the scheduling of time, we spent a lot of time waiting for ourselves and others. In the context of Mandarin, it’s very similar to the phrase “let the bullets fly for a while.” Even grouping took a lot of time; rather than categorizing groups swiftly and violently, we took time and allowed each person to feel today’s needs and make choices. This might sound luxurious in contemporary society, but it shouldn’t be. In those times of collective silence and nothing visible happened, I felt immense relaxation and trust, for which I am deeply grateful.

To summarize my learning in the workshop revolves around the simple act of spending time together and sharing the same space while involving all individuals. However, achieving a more equitable and inclusive environment for Spending and Sharing requires significant time and effort in preparation and communication. Even when preparations are made, the ability to adapt empathetically to the ever-changing states of individuals/groups is challenging. Additionally, whether disability or not, how to place and express feelings and emotions that arise for each person is also a major challenge within this working mechanism.

Experiences working with individuals with disabilities can be directly applied to various artistic or non-artistic collective works, or even in situations where “the self is a collective.” Reflecting on my Lust Body workshop last year, similar needs arose. Perhaps the first step towards creating an organic and inclusive space is to recognize the intersectionality of individuals and groups, create changeable and non-traditional spatial dynamics, allocate sufficient time to foster connections and adopt a more optimistic outlook towards failure.